Book: Nonneoplastic Diseases of Bones

Full article link: https://basicmedicalkey.com/nonneoplastic-diseases-of-bones-3/

Authors: Fiona M. Maclean; S. Fiona Bonar; Peter G. Bullough

ABNORMAL MINERALIZATION

The mineralization of bone depends on several factors, including vitamin D, calcium, phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase; it may be disturbed by the presence of certain metals, such as lead, strontium, iron, and aluminum.

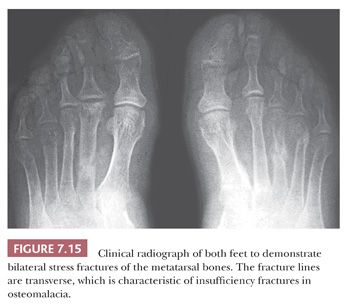

Because routine microscopic examination of bone requires decalcification of the tissue before embedding and sectioning, disease resulting from abnormal mineralization is likely to be overlooked by pathologists unless the clinician has alerted them to the possibility. Plastic embedding can be used to prepare undecalcified sections. If small pieces of only cancellous bone are used, even paraffin-embedded undecalcified tissue may provide adequate sections for diagnosis.

Osteomalacia and Rickets

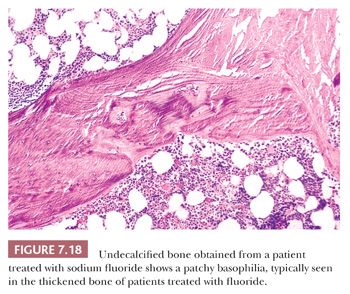

In general, the terms osteomalacia (in adults) and rickets (in children) are used to describe those diseases that result from a deficiency in vitamin D, an abnormality in the metabolism of vitamin D, or a deficiency of calcium in the diet. The most common symptom of osteomalacia is bone pain, which is usually generalized and often vague. In addition, the low calcium level may cause muscle weakness, which is often profound (18). Radiographic examination reveals generalized osteopenia with the classic finding of multiple bilateral and symmetric partial linear fractures of the bone, commonly referred to as insufficiency fractures (Fig. 7.15).

On microscopic examination, the most striking abnormalities are a massive increase in the amount of unmineralized bone (up to 40% or 50% of the total bone volume) and disorganization of the trabecular architecture. The mineralization front, which is the junction between the osteoid and mineralized bone, is very irregular, granular, and fuzzy. In addition to an increase in osteoid volume, bone volume is often increased overall as a consequence of increased osteoblastic activity (Fig. 7.16).

Rickets is the childhood manifestation of osteomalacia. In childhood, the anatomic changes are found most characteristically around the metaphyses of the most rapidly growing bones—that is, around the knee and wrist joints. On x-ray films, the epiphyseal growth plates are irregular and broadened and have a characteristic cup shape. Microscopically, the growth plate is thickened and poorly defined, especially on its metaphyseal side, where tongues of uncalcified cartilage can be seen extending into the metaphysis. As in adults, the bone shows extensive, wide osteoid seams.

In addition to the classic forms of osteomalacia and rickets secondary to calcium and vitamin D deficiencies, severe osteomalacia may occasionally be secondary to hypophosphatemia. Usually, the hypophosphatemia is the result of increased urinary phosphate loss, which may be the consequence of a primary renal tubular defect, diuretic therapy, or hyperparathyroidism. Very rarely, hypophosphatemia is associated with FGF23-producing, phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor, which has been documented in many locations and may be very tiny, resulting in oncogenic osteomalacia. In this instance, resection of the tumor generally results in complete resolution of the osteomalacia. Therefore, it is important to look for an occult tumor in cases of osteomalacia without a clear cause (19–21).

Hypophosphatasia

Hypophosphatasia (not to be confused with hypophosphatemia) is a rare genetic disease characterized by a disturbance in the synthesis of the enzyme alkaline phosphatase (22). It takes two forms. The first is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait that manifests as severe disease in infants. In general, when hypophosphatasia is diagnosed in infants younger than 6 months of age, it follows a rapidly progressive fatal course. The second form is an autosomal dominant condition that may not become evident until adulthood. In these cases, the disease is less severe and often asymptomatic.

The disorder is characterized clinically by decreased levels of alkaline phosphatase in the blood, bone, intestines, liver, and kidneys. The serum phosphorus and calcium levels are usually normal. In less severe cases, hypophosphatasia may not present clinically until the fourth, fifth, or sixth decade of life. Patients often have a childhood history of a rickets-like disorder, short stature, and deformed extremities.

Microscopic examination of the tissue from affected infants reveals increased osteoid and irregular epiphyseal cartilage with lengthened chondrocyte columns. Histopathologic examination of bone from adult patients reveals an osteomalacic picture, with increased quantities of unmineralized bone. Unlike the osteomalacia of vitamin D deficiency, that of hypophosphatasia is characterized by a paucity of osteoblasts.

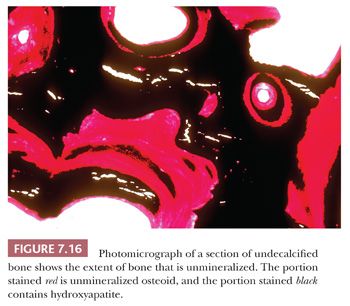

Metal Toxicity

After the introduction of renal dialysis, many patients undergoing this procedure were treated with large doses of antacids to bind dietary phosphate and thereby prevent hyperphosphatemia. Eventually, it became apparent that the aluminum in the antacid had been incorporated into the bone and other body tissues of these patients. Several disease states resulted, most importantly aluminum-induced encephalopathy and aluminum-induced bone disease (23). In aluminum-induced bone disease, the amount of osteoid in the skeletal tissues may be considerably elevated; however, in this form of hyperosteoidosis, unlike that of vitamin D deficiency, the mineralization front is well demarcated, and the osteoblastic activity is minimal. Aurintricarboxylic acid stain can be used to demonstrate aluminum along the mineralization front (Fig. 7.17).

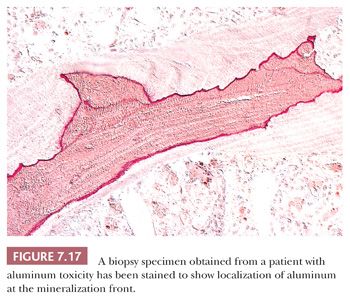

To a much lesser extent, both iron (24) and fluoride interfere with the deposition of calcium within bone. In conditions characterized by high levels of iron (e.g., thalassemia) or fluoride (e.g., fluorosis), osteoid on the surface of the bone is increased (Fig. 7.18).